Anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) injuries are a common concern in sports and physical activities, often requiring extensive rehabilitation and sometimes even surgery. Knee braces are one of the most prescribed devices in the orthotic industry, with medical device companies such as Enovis™ supplying a range of knee bracing solutions for ACL protection and injury prevention. But despite their widespread use, the question remains: Do ACL braces really work?

This article explores the world of ACL braces, examining their purported benefits and the scientific evidence behind their effectiveness, before presenting a new product for people looking to safeguard their knee health.

ACL injury: definition and causes

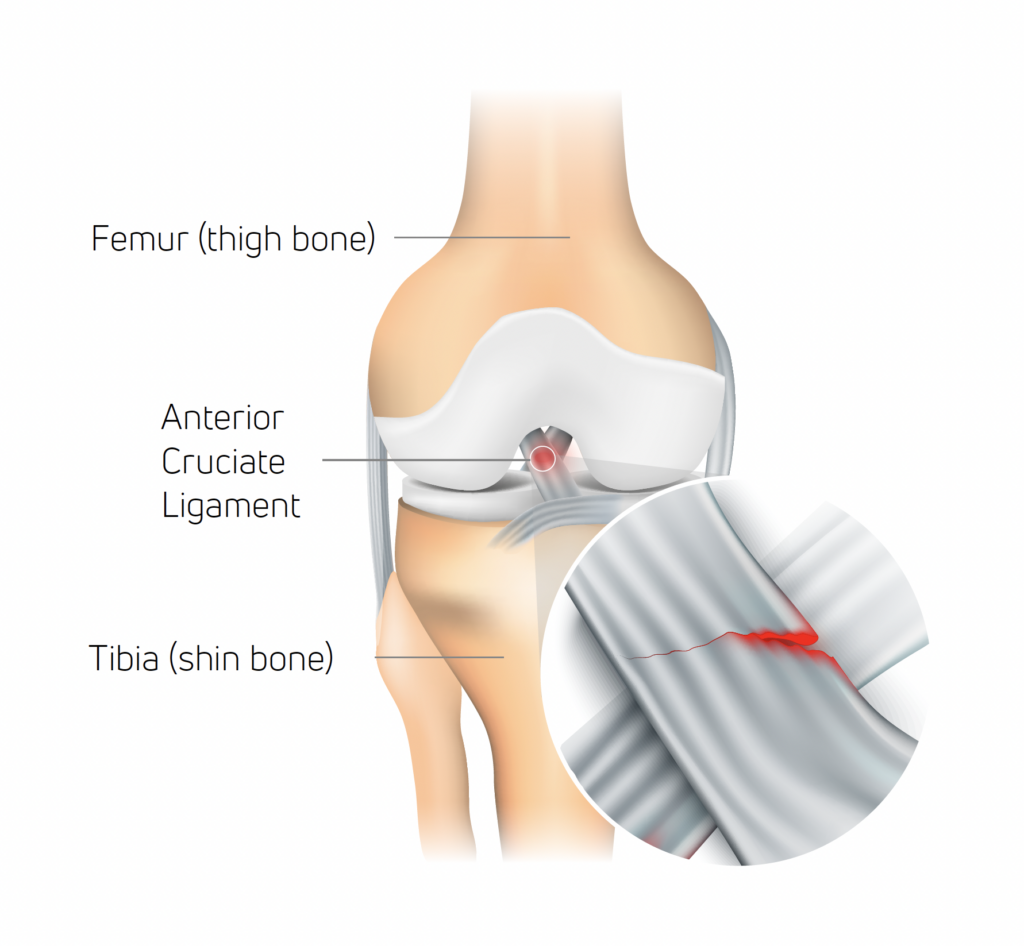

The anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) serves as an essential stabilizer within the knee joint, preventing the tibia (shine bone) from shifting forward in relation to the femur (thigh bone) and ensuring rotational stability.

While an ACL tear can occur due to excessive external force applied to the knee, it’s distinctive in that it can also happen without direct contact, which accounts for 70% of reported ACL injuries1.

In sports like football and other field/court activities, non-contact ACL injuries usually occur during abrupt stops, sudden changes in direction, or when landing from a jump with insufficient knee and hip flexion (at or near full extension)2. The typical scenario involves a combination of deceleration, directional change while the foot is planted, and the knee being near or fully extended. This action can put excessive twisting force on the ACL, leading to strain or rupture.

Evidence that wearing a knee brace can help prevent ACL injury

Clinical studies have demonstrated that wearing a knee brace during activity can help prevent ACL injury as well as protect against reinjury3,4,5.

In a systematic review of current evidence carried out in 2023, Tuang et al. found that protective knee braces were able to control forwards and backwards and sideways knee motion and decrease ACL load/strain during high-risk maneuvers, which may in turn decrease the risk for non-contact ACL injuries3.

With around half of ACL injuries occurring in 15–25-year-olds6, knee bracing effectiveness for young people is a key concern for many. Perrone et al.’s 2019 study involved prescribing knee braces to a group of adolescents post-ACL surgery. The results showed that post-operative use of functional bracing can result in reduced reinjury following ACL reconstruction4.

Bodendorfer et al.’s 2013 study also recommended knee bracing for ACL patients. It found that people with ACL-deficient knees can benefit from the control and proprioception functional bracing can offer. And for highly active athletes participating in high-impact sports, knee bracing further offers protection to the knee ligaments and meniscus during impact from the side5.

How DonJoy® knee braces help prevent ACL injury

DonJoy® is a name synonymous with knee bracing. A key brand of Enovis, it has been manufacturing and supplying braces for knee ligament protection since the late 1970s, using patented technology that reduces ACL strain.

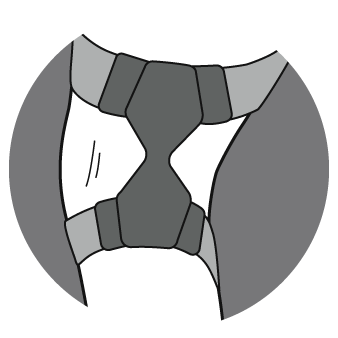

The Four-Points-of-Leverage™ system featured in DonJoy knee braces consists of a rigid cuff and strap configuration. Through this, a posterior force is applied to the tibia, which prevents anterior movement and reduces the strain on the ACL7.

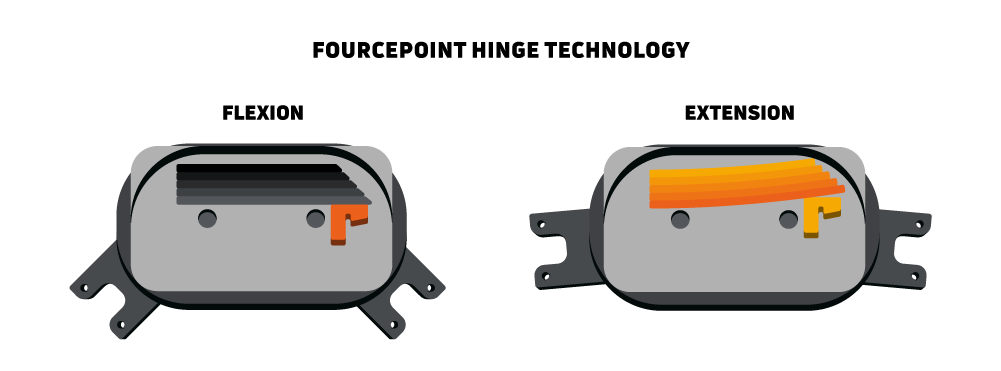

The second key technology in DonJoy knee braces is the FourcePoint® hinge. This complements the Four-Points-of-Leverage design by damping knee joint extension, which improves the mechanical performance of the brace and reduces shear forces at the knee. The hinge resistance kicks in during the last 25 degrees of knee extension, targeting the vulnerable “at-risk” position.

When combined, the FourcePoint hinge and the Four-Points-of-Leverage design create a more comfortable brace that diminishes anterior shear forces on the knee. This stability is particularly advantageous for people wanting to prevent ACL injuries during activity and those recovering from ACL injuries, as it eases strain on the deficient or healing ACL graft8,9.

Defiance® PRO: custom knee ligament bracing from DonJoy

When it comes to ligament knee bracing, few product names stand out more than Defiance®. Alongside off-the-shelf alternatives, DonJoy’s flagship custom brace has been protecting knees for decades. Now with the Defiance® PRO taking the design to the next level, those looking to prevent ACL injuries have a new name to trust in.

Featuring the proven Four-Points-of-Leverage and FourcePoint technologies, Defiance PRO also provides a range of customizable elements to offer patients an enhanced wearing experience.

Every Defiance PRO order begins with the patient receiving a precise measurement of their leg from an Enovis representative. These measurements are then used to build a brace exactly matched to the customer’s leg for an even closer and more comfortable fit.

Patients can further tailor their brace by choosing the frame colour from over 30 available options and adding a series of accessories, including a sports cover and silicone condyle pads for extra comfort.

With this combination of clinically proven technology and superior craftmanship, patients can be confident that DonJoy is the name to trust for knee ligament bracing.

To learn more about DonJoy knee braces, visit our website.

References

- Boden BP, Dean GS, Feagin JA Jr, Garrett WE Jr. Mechanisms of anterior cruciate ligament injury. Orthopedics. 2000 Jun;23(6):573-8.

- Silvers, H. J., & Mandelbaum, B. R. (2007). Prevention of anterior cruciate ligament injury in the female athlete. British journal of sports medicine, 41 Suppl 1(Suppl 1), i52–i59.

- Tuang, B.H.H., Ng, Z.Q., Li, J.Z., Sirisena D. (2023). Biomechanical Effects of Prophylactic Knee Bracing on Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injury Risk: A Systematic Review. Clin J Sport Med. Jan 1;33(1):78-89.

- Perrone, G.S., Webster, K.E., Imbriaco, C., Portilla, G.M., Vairagade, A., Murray, M.M., Kiapour, A.M. (2019). Risk of Secondary ACL Injury in Adolescents Prescribed Functional Bracing After ACL Reconstruction. Orthop J Sports Med. Nov 12;7(11):2325967119879880.

- Bodendorfer, B.M., Anoushiravani, A.A., Feeley, B.T., Gallo, R.A. (2013). Anterior cruciate ligament bracing: evidence in providing stability and preventing injury or graft re-rupture. Phys Sportsmed. Sep;41(3):92-102.

- Griffin LY, Albohm MJ, Arendt, EA, et al. (2006). Understanding and Preventing Noncontact Anterior Cruciate Ligament Injuries: A Review of the Hunt Valley II Meeting, January 2005. Am J Sports Med 34(9):1512-32

- Fleming, B. C., Renstrom, P. A., Beynnon, B. D., Engstrom, B., & Peura, G. (2000). The influence of functional knee bracing on the anterior cruciate ligament strain biomechanics in weightbearing and nonweightbearing knees. The American journal of sports medicine, 28(6), 815–824.

- Théoret, D., & Lamontagne, M. (2006). Study on three-dimensional kinematics and electromyography of ACL deficient knee participants wearing a functional knee brace during running. Knee surgery, sports traumatology, arthroscopy : official journal of the ESSKA, 14(6), 555–563.

- Stanley, C. J., Creighton, R. A., Gross, M. T., Garrett, W. E., & Yu, B. (2011). Effects of a knee extension constraint brace on lower extremity movements after ACL reconstruction. Clinical orthopaedics and related research, 469(6), 1774–1780.