For decades, plaster casts have been the default choice for immobilizing lower-limb injuries such as Achilles tendon ruptures and ankle fractures. However, growing clinical evidence suggests that functional walker boots offer a cost-effective alternative without compromising patient outcomes or safety.

So what does the latest research actually tell us? And how should this influence treatment decisions in modern orthopedic care?

Rethinking Immobilization: Why Cost-Effectiveness Matters

Healthcare systems are under increasing pressure to deliver high-quality outcomes while controlling costs. Immobilization strategies play a significant role in this equation, not just in terms of device cost, but also:

- Time and resources required for application and removal

- Follow-up appointments and unplanned hospital visits

- Need for informal care and support

- Speed of functional recovery and return to work

Multiple studies now indicate that walker boots consistently perform well across these areas, particularly when early weight-bearing protocols are used.

Achilles Tendon Rupture: Comparable Outcomes, Lower Overall Costs

One of the most robust datasets comes from the UKSTAR trial by Costa et al.1, a large multicenter randomized controlled study involving 527 patients across 39 NHS hospitals. The trial compared:

- Traditional plaster casting (8 weeks, delayed weight bearing)

- Functional walker boot (8 weeks, immediate weight bearing)

Key findings:

- Total health and social care costs were slightly lower in the walker group (by approximately £103 per patient), although the difference was not statistically significant

- No difference in functional outcome at 9 months, measured using the Achilles Tendon Total Rupture Score (ATRS)

- No difference in re-rupture rates, confirming comparable safety profiles

In other words, functional bracing delivered equivalent clinical results at a lower or comparable cost, while enabling earlier mobilization.

Importantly, clinicians concluded that early weight-bearing in a walker boot can be considered a safe and cost-effective alternative to plaster casting.

Why Walker Boots May Support Better Recovery

The cost-utility advantage of walker boots is not purely financial, it is closely linked to how patients recover.

Evidence suggests improved functional recovery may be related to:

- Greater comfort and convenience for patients2

- Compatibility with early weight-bearing protocols1,3,4

- Ability to remove the boot for controlled mobilization exercises1,5,6

- Reduced reliance on informal carers7

These factors can translate into faster return to normal activity and work1,4,7, which has major societal and economic implications beyond direct healthcare costs.

Ankle Fractures: Strong Evidence Across Operative and Non-Operative Care

The evidence is equally compelling for ankle fractures. A UK multicenter randomized trial evaluated cast immobilization versus walker boots in 669 patients across 20 NHS trauma units.

Clinical outcomes:

- No significant difference in functional outcomes at 4 months or 2 years8,9

- Functional outcomes measured using the Olerud-Molander Ankle Score (OMAS) were equivalent8,9

- Complication rates were similar between cast and walker groups8,9

Economic outcomes:

- Cost-utility analysis showed that, from an NHS perspective, removable braces were cost-effective under commonly accepted willingness-to-pay thresholds10

The authors concluded that a removable walker boot is as effective and safe as a plaster cast, for both operative and non-operative ankle fracture management, and remains so in the long term.

Post-Operative Ankle Fractures: The Case for Early Weight Bearing

Recent studies have added another important dimension: timing of weight bearing.

Two major UK trials provide valuable insights:

1. Ankle Recovery Trial (ART)

- Compared walker boots versus casts after ankle fracture surgery

- Found the total treatment cost per patient was £676 lower in the walker group

- Analysis included not only device cost, but also informal care and productivity losses

2. Weight-bearing in Ankle Fracture (WAX) Trial

- Compared early vs delayed weight bearing post-operatively

- Early weight bearing was associated with £722 lower mean societal costs, largely due to reduced work absence

Taken together, these findings suggest that early weight bearing in a walker boot may offer substantial cost savings compared to delayed weight bearing in a cast, without compromising safety or outcomes4,7.

What This Means for Clinical Practice

Across Achilles tendon rupture and ankle fracture management – both conservative and post-operative – the evidence consistently shows that walker boots:

- Are at least as effective as plaster casts

- Offer comparable safety profiles

- Support earlier mobilization and weight bearing

- Can deliver meaningful cost savings, especially when societal costs are considered

For clinicians and healthcare systems alike, this supports a shift toward functional immobilization strategies where clinically appropriate.

Conclusion: Walker Boots are Evidence-Based, Patient-Centered, Cost-Effective

Modern functional walkers allow clinicians to align clinical outcomes, patient experience, and economic efficiency. As the evidence base continues to grow, walker boots are increasingly positioned not as an alternative, but as a first-line option for many lower-limb injuries.

As always, individual patient factors and clinical judgement remain paramount, but the data clearly supports giving functional bracing serious consideration in contemporary orthopedic care.

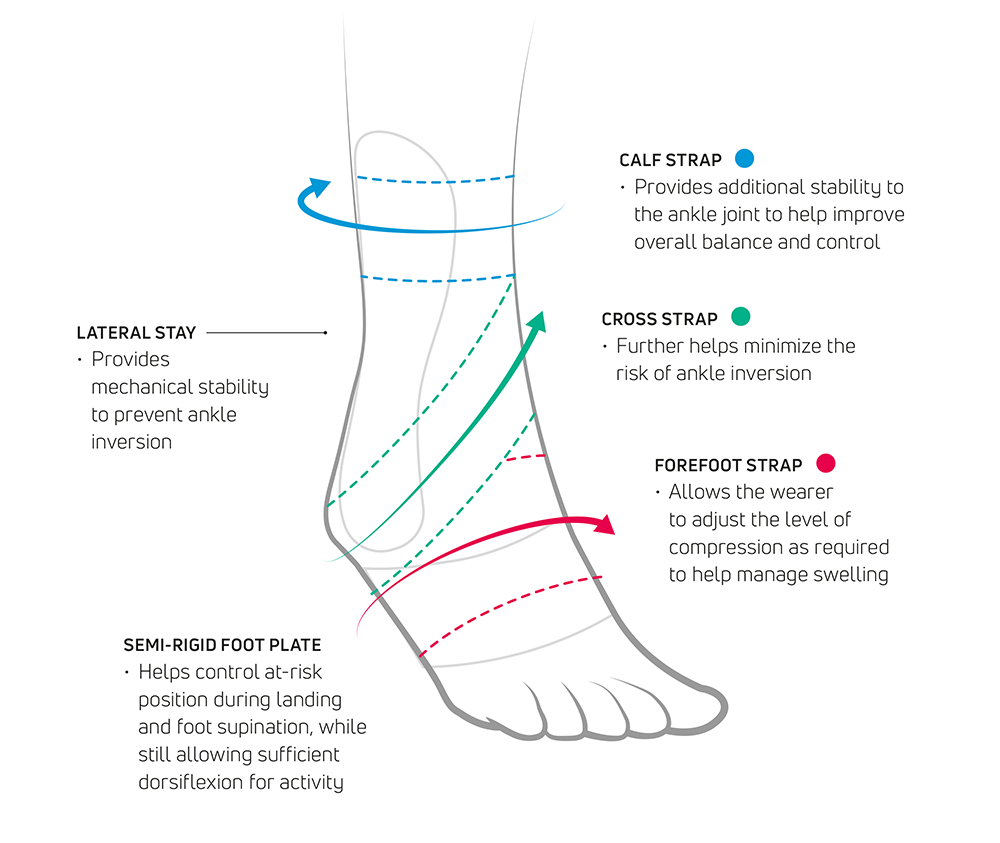

DonJoy® Nextep Xcel™: a New Cost-Effective Walker Range from Enovis™

Healthcare professionals need dependable orthopedic solutions that are designed to deliver consistent patient outcomes while remaining practical. The new DonJoy® Nextep Xcel™ range meets these needs through a family of full-shell walker boots for post-operative and post-trauma foot and ankle care.

By integrating established technology with streamlined design, Nextep Xcel offers a comprehensive approach to patient mobility management. The range provides the clinical performance clinicians expect while supporting efficiency within practices.

The Nextep Xcel range represents a balanced approach to orthopedic care, delivering the functionality patients need and the reliability clinicians value.

For more information on Enovis’s portfolio of orthopedic walker boots, visit our website or contact your local Enovis representative.

References

- Costa ML et al. UKSTAR trial collaborators. Plaster cast versus functional brace for non-surgical treatment of Achilles tendon rupture (UKSTAR): a multicentre randomised controlled trial and economic evaluation. Lancet. 2020 Feb 8;395(10222):441-448.

- Hampton MJ et al. Functional Walker Boots are Preferred to Synthetic Casts by Patients and Carers in the Management of Pediatric Stable Ankle Injuries. J Pediatr Orthop. 2024 Feb 1;44(2):99-105.

- Ghaddaf AA et al. Early versus late weightbearing in conservative management of acute achilles tendon rupture: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Injury. 2022 Apr;53(4):1543-1551.

- Bretherton CP et al. WAX Investigators. Early versus delayed weight-bearing following operatively treated ankle fracture (WAX): a non-inferiority, multicentre, randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2024 Jun 29;403(10446):2787-2797.

- Egol KA et al. Functional outcome of surgery for fractures of the ankle. A prospective, randomised comparison of management in a cast or a functional brace. J Bone Joint Surg Br. 2000 Mar;82(2):246-9.

- Barile F et al. To cast or not to cast? Postoperative care of ankle fractures: a meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Musculoskelet Surg. 2024 Dec;108(4):383-393.

- Baji P et al. Use of removable support boot versus cast for early mobilisation after ankle fracture surgery: cost-effectiveness analysis and qualitative findings of the Ankle Recovery Trial (ART). BMJ Open. 2024 Jan 11;14(1):e073542.

- Kearney R et al. AIR trial collaborators. Use of cast immobilisation versus removable brace in adults with an ankle fracture: multicentre randomised controlled trial. BMJ. 2021 Jul 5;374:n1506.

- Nwankwo H et al. Cost-utility analysis of cast compared to removable brace in the management of adult patients with ankle fractures. Bone Jt Open. 2022 Jun;3(6):455-462.

- Haque A et al. the AIR Trial collaborators. Use of cast immobilization versus removable brace in adults with an ankle fracture: two-year follow-up of a multicentre randomized controlled trial. Bone Joint J. 2023 Mar 15;105-B(4):382-388.